On Thoughts And Feelings

When we think of Mental Processes, we might start to look at an obvious place:

That is, Cognition (Thinking)

And then, naturally, it seems the next step would be:

Meta Cognition (Thinking about thinking), and so on.

This meta-cognition seemingly can be experienced in some situations simultaneously, or after thinking. This is often immediately after, but maybe also some time later, e.g. we remember what we thought, and then we start thinking about that thought.

Another side of this, though, which seems obvious but sometimes gets lost, is that both of these processes may be accompanied by feelings or “sentiments” (as David Hume called them).

Adding these to the basic model of mental processes gives us maybe some more interesting interactions between them, and might help understand how we might get so confused, overwhelmed, and reactive.

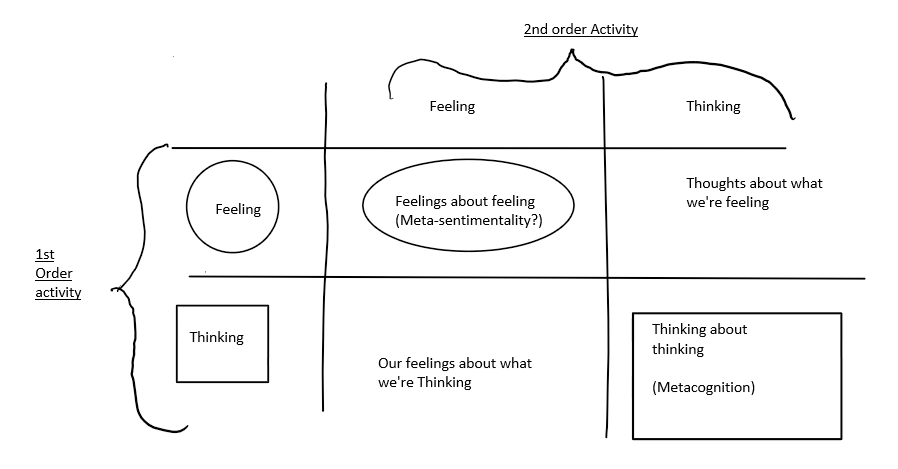

See below:

We can see from the above table that we don’t really have a word for our “feelings about our feelings”. I propose “meta-sentimentality”. It’s probably already been coined, since it’s an obvious equivalent to “meta-cognition.”

Also, in reality, our thoughts and feelings are not necessarily so distinct, for example, you might be having the feeling of love, and the thought of “I am happy” might also exist and be mixed up in that. However, the thought of happiness could arise on reflection of the experience of feeling love, or similarly you experience the feeling of love due to the fact that you have the thought that “I am happy”.

We can also continue to go further than just two layers as well, we can think about the way we think about our thoughts, i.e. “meta- meta-cognition”, and perhaps it’s the same for feelings, giving us an even busier and more involved picture. The further we go, the more things are combined the more likely we’d be to get confused by it all.

But perhaps this “spiralling” of thoughts can be stopped in its tracks through another set of experience.

This aspect of experience I haven’t considered here so far and is perhaps more powerful than either thinking or feeling is the experience of sensation. Sensations are our immediate sense-perceptions, and exist outside these thoughts and feelings. It’s tempting to say they are outside the “mental space” entirely, perhaps embodied throughout our nervous system. Hence they are able to be used in practices such as mindfulness that ground people who are feeling otherwise overwhelmed with the mental processes of thought and feeling.

For example, we don’t neeed to understand that something is hot before we move our hand away from it. It can easily dominate over feeling and thought in our mental space, which may be a good thing.